There Are Two Ways to Lose Weight

Why one relies on willpower and calorie counting—and the other changes how your body fuels itself.

Mr. Skeptical rolls his eyes.

“Are you suggesting that there are only two diets out there, when I hear of a different diet every other week?”

That’s not what I’m saying. There are plenty of different diets, but only two dominant ways to lose weight.

Subconscious Fat at 30,000 feet

The first and most common way to try to lose weight is by creating a caloric deficit—eating fewer calories than you burn, often while continuing to eat carbohydrates and sugar.

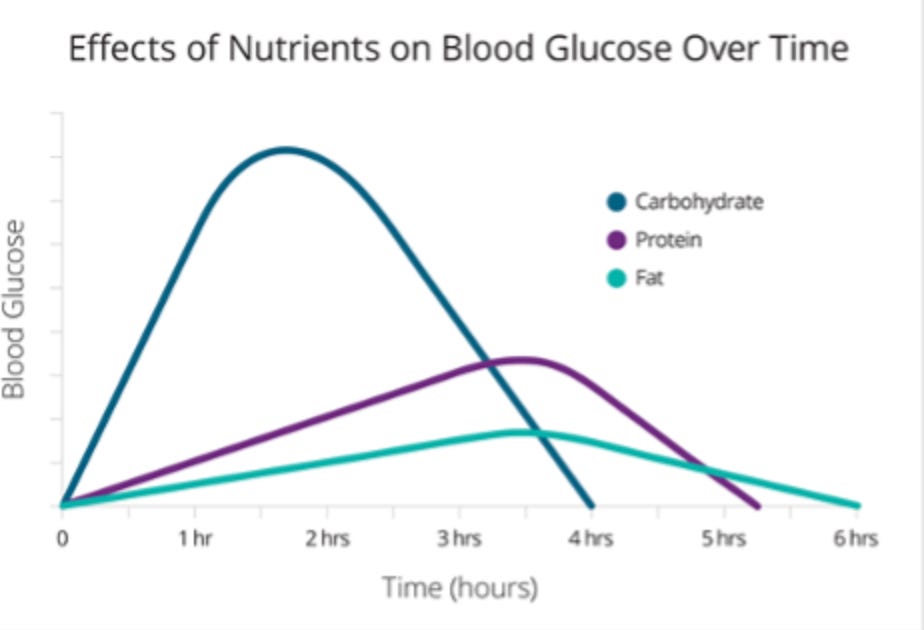

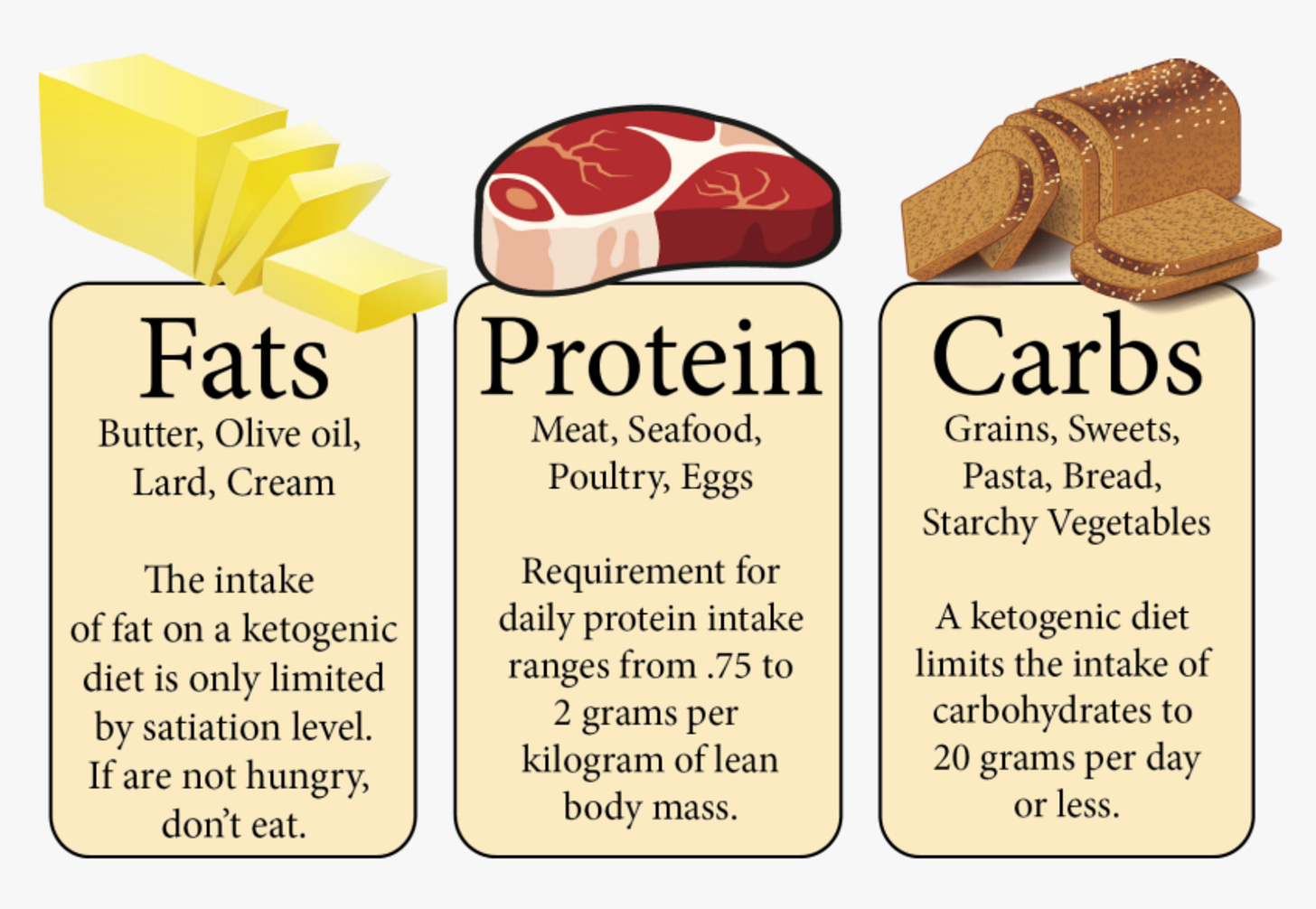

The other is by shifting the body into ketosis—lowering carbohydrates enough that fat becomes the primary fuel source.

On paper, both methods can work.

But in real life, they feel radically different.

And that difference—how they feel—is usually what determines whether someone stays consistent or quietly quits.

Subconscious Fat at 10,000 feet

The caloric deficit model is the most widely accepted.

Eat less.

Move more.

Track intake.

Trust the math.

Mr. Skeptical immediately clears his throat.

“Calories in versus calories out. That’s basic physics.”

True.

But physics doesn’t account for hunger, energy crashes, cravings, stress, or decision fatigue.

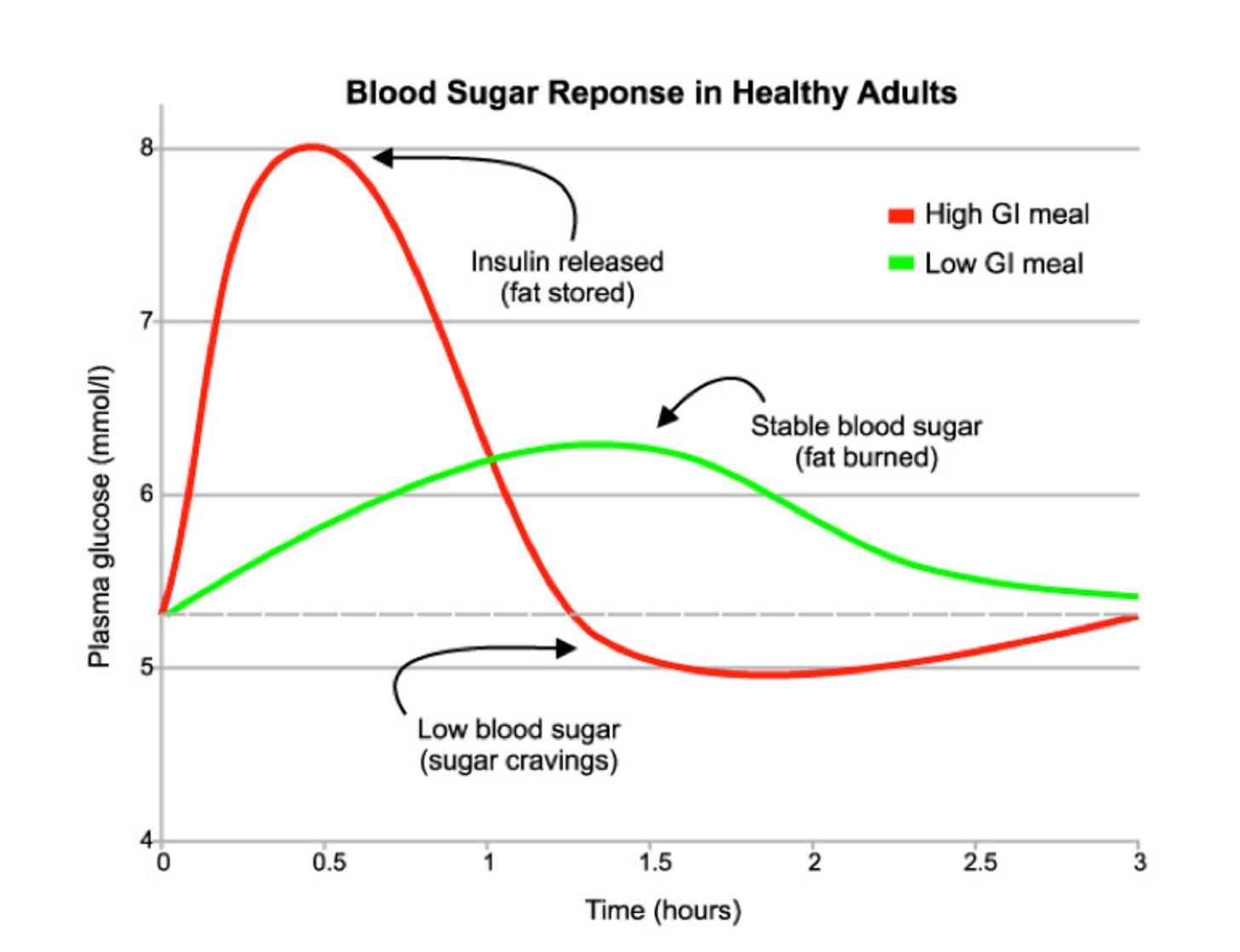

A caloric deficit—especially one that includes significant carbohydrates and sugar—often requires constant vigilance. You’re managing portions, tracking numbers, and resisting appetite signals that never really quiet down.

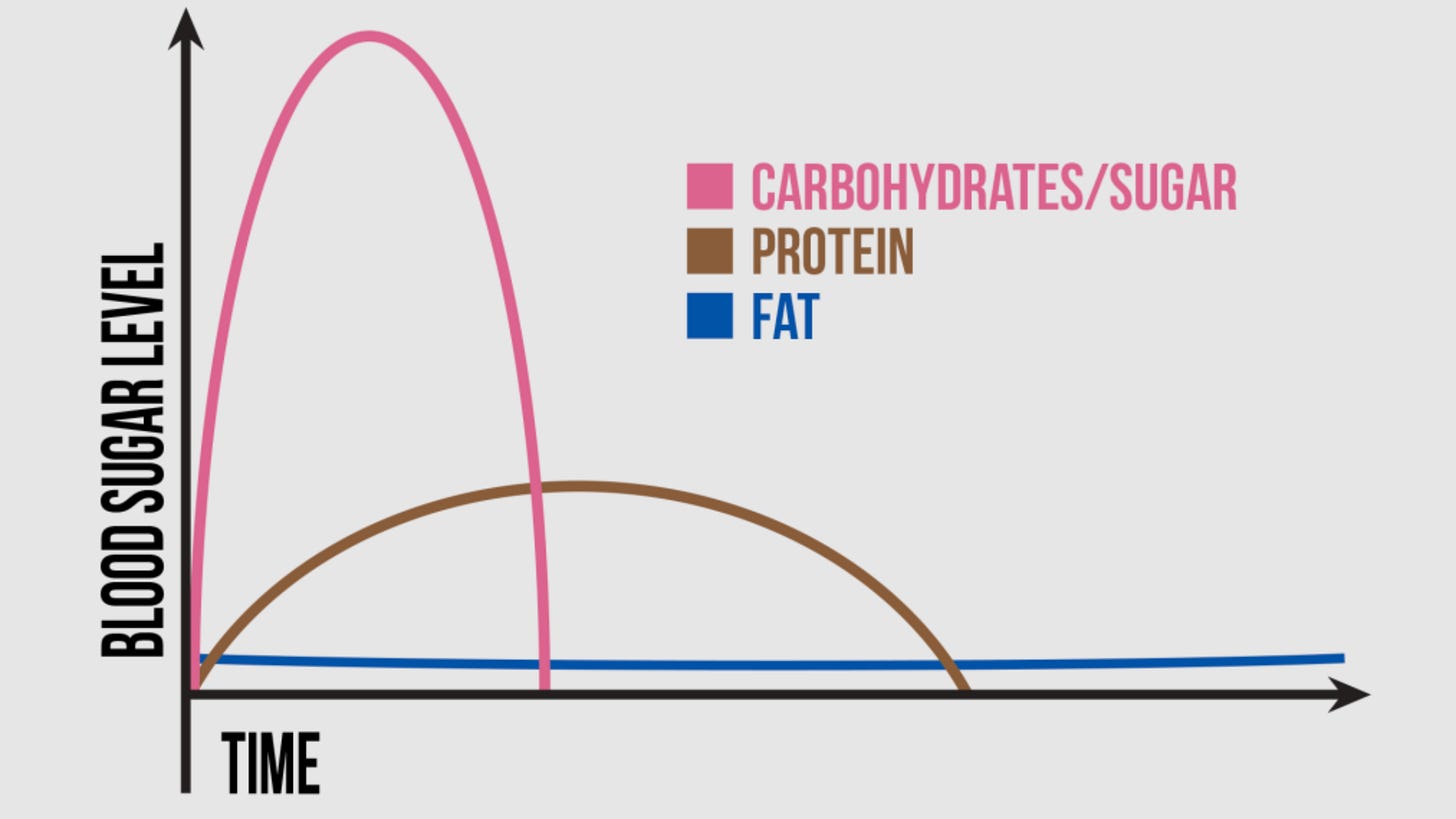

Ketosis approaches the problem differently.

Instead of forcing the body to run on glucose while restricting intake, it changes the fuel system entirely. By keeping carbohydrates very low, insulin drops and stored fat becomes accessible. Appetite often becomes calmer—not because of discipline, but because physiology shifts.

Same math.

Different experience.

Subconscious Fat at Eye-Level

Here’s where most people actually live.

A caloric deficit requires you to fight hunger while staying mentally engaged all day long. Every meal is a calculation. Every snack is a negotiation. Progress depends heavily on willpower.

Mr. Skeptical raises an eyebrow.

“So you’re saying people fail because they lack discipline?”

Not exactly.

They fail because the system requires too much discipline for too long.

Ketosis removes a large amount of friction. Meals become simpler. Hunger becomes predictable. Energy stabilizes. Many people report feeling less urgency around food—not because they’re trying harder, but because their body isn’t constantly asking for sugar.

That doesn’t mean ketosis is effortless. It requires clear food boundaries and fewer options.

But fewer options often mean fewer decisions.

And fewer decisions mean better consistency.

Mr. Skeptical leans back.

“Simple doesn’t mean easy.”

Correct.

But easier beats harder when long-term adherence is the real goal. In Occam’s Razor Fitness, I tell my clients it’s not about a new ‘diet’, it’s about a new lifestyle.

Practical Suggestions and Conclusions

Both approaches obey the same laws of energy balance.

Calories still matter.

Physics still applies.

The difference is not whether fat loss happens—but how sustainable the process feels over weeks and months.

Mr. Skeptical sighs.

“Are you saying this is why so many people yo-yo diet. They lose the weight, and then it comes back with a vengeance.”

I smile, enjoying a rare moment where he’s agreeing with me.

A caloric-deficient diet is usually too much work.

And for many—especially those who’ve dieted repeatedly—it becomes mentally exhausting.

Ketosis shifts the burden away from constant restraint and toward metabolic alignment. When fat becomes fuel, hunger often fades into the background. Meals stop feeling urgent. Skipping food doesn’t feel like punishment.

Mr. Skeptical nods reluctantly.

“So the advantage isn’t magic—it’s compliance.”

Exactly.

The best diet isn’t the one that works in theory.

It’s the one you can live with when life gets busy, stressful, or inconvenient. It’s the diet you can turn into a lifestyle.

Ketosis doesn’t eliminate effort—but it tends to reduce friction. And in a world full of friction, that matters more than most people want to admit.

The real takeaway isn’t that one method is morally superior.

It’s that systems that work with human biology tend to outperform systems that rely on constant self-control.

Mr. Skeptical shrugs.

“I still like my math.”

That’s fine.

Just don’t forget the human being on the other side of the equation.

Be aware.

Other links related to this post:

Food = Fuel + Taste

How Much Fat Should We Eat?

5,700 Years Ago, Dinner Was HumanPS Links on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X, and Notes. Full disclosure: ChatGPT was used to research and enhance this post.

I’m so happy to see Mr. Skeptical is still at it!