5,700 Years Ago, Dinner Was Human

Archaeology shows meat was so essential, even humans weren’t off the menu.

My LinkedIn account is currently suspended. If we met online via LinkedIn, please add me to your Facebook, Instagram, X, and Notes, where I continue to post content. “Wait—you’re telling me people in Spain were still eating people only a few thousand years ago? That’s basically… yesterday in evolutionary time.”

Mr. Skeptical looks like he just found out his tapas plate might have a dark backstory.

“That’s right. A recent study published in Nature (2024) uncovered evidence of cannibalism in a 5,700-year-old site in Spain. Unlike the 800,000-year-old Atapuerca bones of Homo antecessor, this was no archaic cousin. These were modern humans. Farmers. Pottery users. People who looked like us.

And yet—cut marks, burned bones, marrow extraction. Same as before. Same story: human flesh treated like animal flesh.”

Subconscious Fat at 30,000 feet

Now, here’s where modern sensibilities trip us up. We imagine cannibalism as psychopathic, grotesque, the final breakdown of civilization. But to our ancestors, it was Tuesday.

“Tuesday tacos… but made of Todd?”

Sometimes Mr. Skeptical goes a little too far.

Cannibalism unsettles us because it breaks the last taboo. We want to believe there’s a sharp line between “civilized” and “savage,” between modern humans and our distant ancestors. But discoveries like this blur that line.

Five thousand years ago—around the time Egypt was building pyramids—people in Spain were butchering other people for food.

Mr. Skeptical adds, “Talk about the original Mediterranean diet.”

He never misses the chance for a punchline.

“The big picture? Humans are meat seekers. Always have been. And when times got tough—or enemies got close—meat was meat.”

Subconscious Fat at 10,000 feet

Mr. Skeptical crosses his arms, “But why eat other humans? Isn’t that crossing a line?”

“Here’s the key: you don’t eat your own. You eat the other. Cannibalism required dehumanization—turning neighbors, rivals, or captives into calories instead of comrades.

“This is war cannibalism, not famine cannibalism. Evidence from the site suggests a violent context—killings followed by butchering. The victims weren’t just unlucky; they were enemies.

“That instinct to divide the world into “us” and “them” has deep evolutionary roots. It made survival possible. And in this case, it made dinner possible.”

Mr. Skeptical shakes his head, “But to eat another human that looks like you?”

“Normally, you wouldn’t do that, but here’s another wrinkle: war cannibalism likely required mental gymnastics. It’s hard to eat your own kin. But your rivals? The out-group? The tribe across the valley? They aren’t “real” humans. They’re meat on legs.

And that psychological trick—dehumanization—may have been as important to our survival as the flint knife. We had to divide the world into us and them. And sometimes “them” ended up as dinner.

Mr. Skeptical smiles, “Just imagine the first awkward dinner invitation: ‘Don’t worry, it’s not anyone you know.’”

Subconscious Fat at Eye-Level

The bones tell the same story they always do:

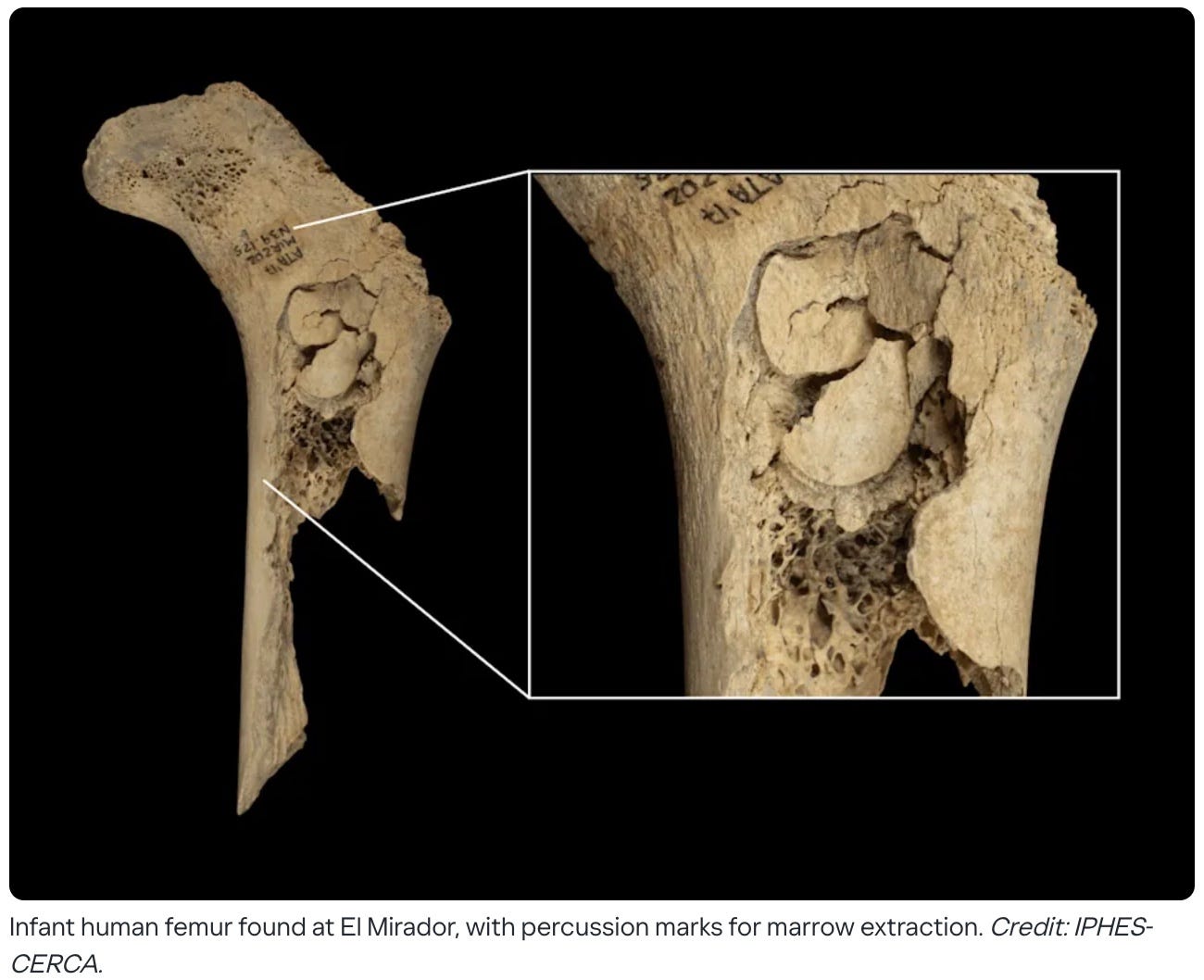

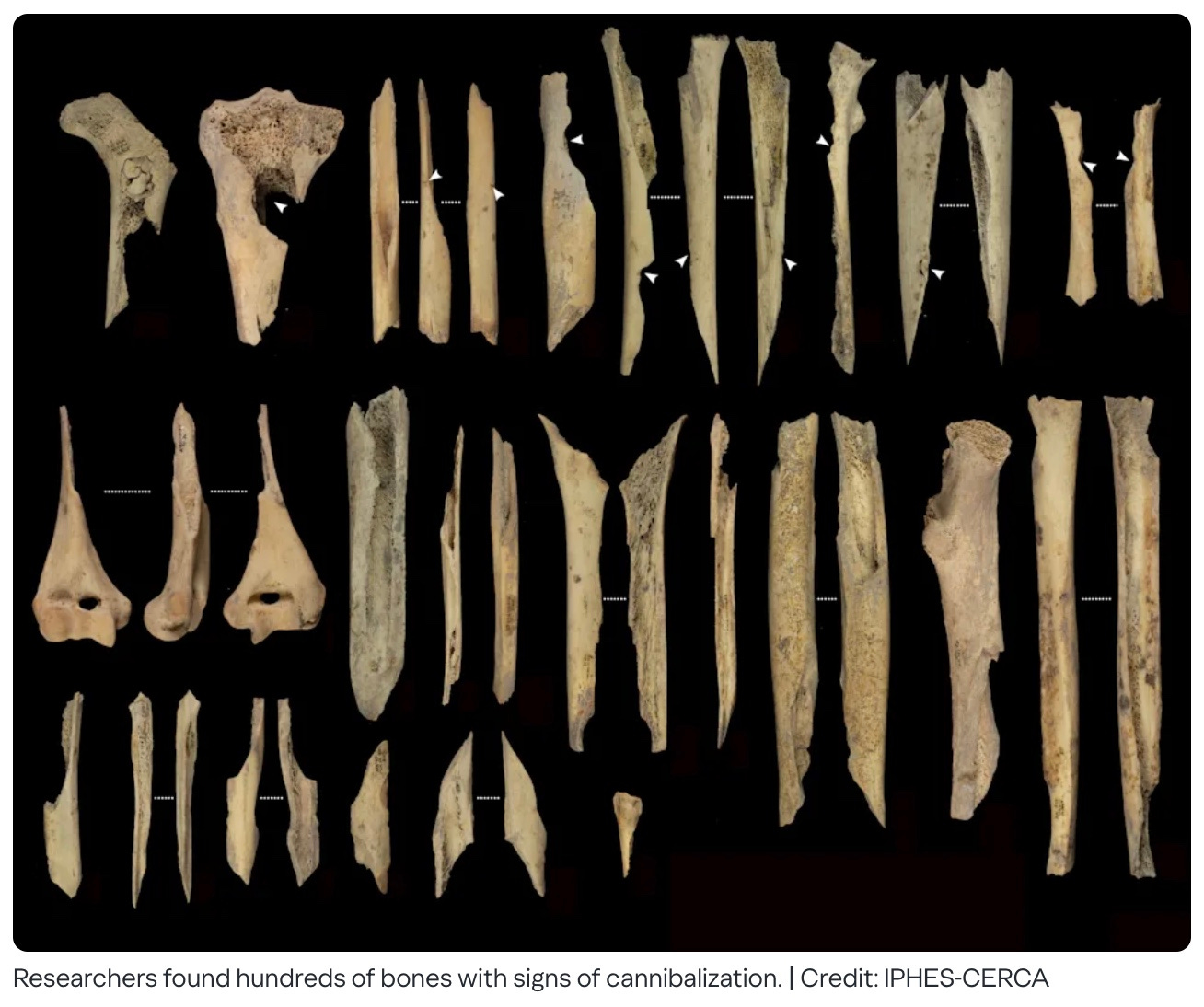

Cut marks identical to those left on animal carcasses.

Burning patterns consistent with roasting. Some bones were translucent with slightly rounded edges, suggesting boiling.

Fractured long bones—not random violence, but marrow extraction.

Translation: this wasn’t ritual, wasn’t symbolic. It was practical. Calories were scarce, protein and fat were precious, and humans weren’t exempt from the menu.

Think about it: you don’t risk infection, social taboo, and cosmic punishment for fun. You do it because the nutritional return is worth it.

Mr. Skeptical sighs, “I just can’t imagine eating Bob.”

“I’m not suggesting you make Jeffrey Dahmer a role model. But consider this: mainstream health advice is constantly nudging us away from meat. Less red meat, more grains, less fat, more fiber. Yet human history screams the opposite. Meat was prized, hunted, fought over, and, if necessary, taken from other humans.

Our physiology still reflects that drive.

We digest animal fat efficiently.

We crave protein to the point of overeating carbs when it’s too low (the “protein leverage hypothesis”).

Our brains are built from DHA, B12, and heme iron—nutrients only dense in meat.

That doesn’t vanish because a government pyramid chart says so.

Practical Suggestions and Conclusions

So here’s how to take the lesson from cannibals in Spain without booking a one-way trip to solitary confinement:

Prioritize Meat Like They Did. Steak, lamb, venison, fish, eggs. Make it central. Don’t apologize.

Respect Fat as Fuel. Marrow, suet, fatty cuts—our ancestors cracked bones for this. Stop fearing it.

Don’t Other Yourself. Modern humans don’t need to fight tribes across the valley, but they do need to resist the dietary dogma that treats meat eaters like cavemen. Stand your ground.

Train for the Hunt. You don’t need a spear, but you do need muscle. Muscle is how you carry the kill—or in our case, carry groceries and keep blood sugar stable.

The message is clear: we are built on meat. So built on it that even other humans weren’t safe from the menu.

Humans ate humans. It wasn’t because they were monsters. It was because they were hungry, and because meat is essential.

The real monstrosity isn’t always what happened in the human past. The real monstrosity is today, when doctors warn you against steak but hand out statins like candy.

“Yeah, but at least statins don’t eat you back.”

“True. But at least steak tastes good.”

Be aware.

Other links related to this post:

Omnivores Survive, But Carnivores Thrive

Does What We Eat Affect Mental Health

animal.

PS Links on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X, and Notes. Full disclosure: ChatGPT was used to research and enhance this post.